The Problem

In-person conferences can be expensive and difficult to organize, making some wonder whether they are worth the cost and time.

In-person conferences can be expensive and difficult to organize, making some wonder whether they are worth the cost and time.

A model that optimizes team organization to get the most from both in-person and virtual events.

Productive teams can create valuable and worthwhile scientific breakthroughs.

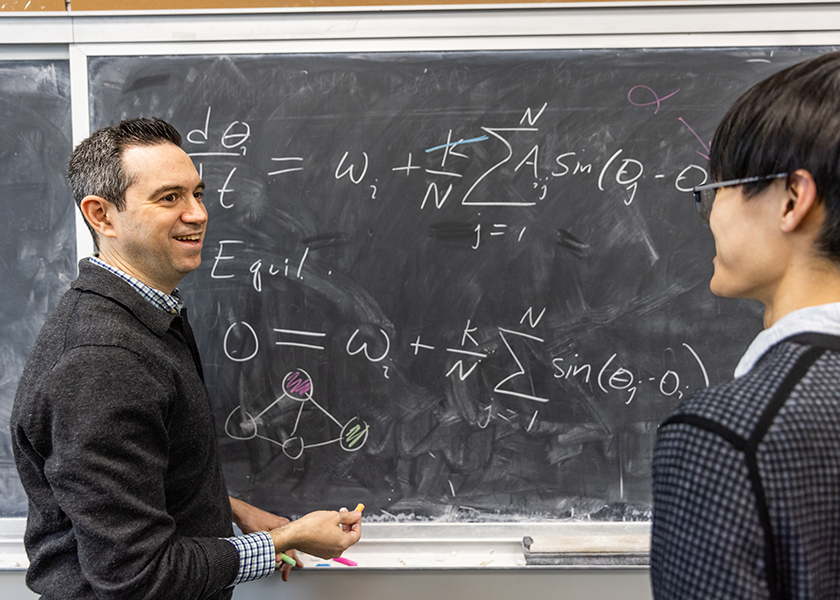

Professor Daniel Abrams

The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on all aspects of society, some of which have remained even as the virus has largely been controlled. One of them is how we conduct business meetings and even conferences, as virtual get-togethers have become commonplace.

But is there value in traditional in-person events? Recent research from Northwestern Engineering’s Daniel Abrams says yes, especially if conference organizers know how to assemble the right teams.

“The public may wonder, as I once did, if there is actually any value in conferences beyond tourism,” Abrams said. “It turns out that there is strong evidence that conferences — at least scientific conferences — really do build community and spark new ideas and new collaborations.”

Abrams presented his work in the paper “Face-to-Face or Face-to-Screen: A Quantitative Comparison of Conferences Modalities,” which was published recently in the journal PNAS Nexus. Abrams, who holds the Bette and Neison Harris Chair in Teaching Excellence, is a professor of engineering sciences and applied mathematics at the McCormick School of Engineering, and is codirector of the Northwestern Institute on Complex Systems (NICO). Emma Zajdela (PhD ’23), a postdoctoral research fellow at Princeton University, was the paper’s first author.

Unlike virtual meetings, in-person conferences can be expensive for organizers and attendees, difficult to schedule, and have the appearance of just being an excuse for people to travel on their employer’s dime to hang out with friends and colleagues. Virtual conferences also allow remote attendance for people who cannot travel due to cost, child care, or other scheduled responsibilities.

Yet face-to-face contact has significant value. Abrams, Zajdela, and their colleagues found that formal interaction in assigned discussion groups has a strong impact on the formation of new scientific teams, something that is true at both virtual and in-person conferences. In-person conferences, however, are more conducive to building community, as attendees get to know a larger fraction of the other attendees.

“These findings reveal the important role played by conference conveners,” Abrams said. “Their organizational choices influence team formation and thus may have an impact on science for years into the future.”

Building on his group’s work developing a mathematical model for team formation, Abrams and his colleagues drew on data from multiple virtual and in-person conferences held over six years, spanning from before, during, and after the pandemic. Using three criteria – team formation, engagement, and community building – the team looked at statistics from a series of conferences dubbed “Scialogs” that span a wide range of scientific fields. The data captured detailed information from more than 12,000 pairs of participants, including their demographics, pre- and post-conference awareness of one another, assigned discussion sessions, and formation of new collaborations. A second dataset encompasses more than 250,000 pairs of participants who spoke in sessions at the American Physical Society March Meeting and their publication records.

The result was that formal interaction impacted team formation significantly more in virtual settings, while informal interaction played a larger role at in-person conferences as compared to virtual. The group also tested eight models for predicting which conference attendees will team up, finding the one that worked the best.

“Our findings move the field forward by clarifying the benefits and drawbacks of virtual conferences,” Abrams said. “Our model also allows future conference organizers to make the best use of attendees' time by creating agendas based on these results.”

Abrams is currently studying how conversations lead to team formation, how people take turns in those conversations, and whether that information can improve the predictions of the model for who will team up.

“The idea is to inform facilitators so that discussions can be made more effective, with potential impact beyond this specific scientific setting to the larger questions of what leads to effective communication and effective teaching,” Abrams said.