Inside The Mouse-Hunting Mission

Dilan Wijesinghe’s final MSR project advanced robotics research that could help increase understanding of complicated mental health issues.

Dilan Wijesinghe (MSR ‘23) thought he had the mouse cornered.

Peeking around an obstacle, he locked eyes with the rodent and, with a sudden burst, closed the distance between him and his target.

But the mouse quickly developed a plan. A quick feint to the left threw Wijesinghe a tick off-balance. The rodent then went hard-right, wove around an obstacle, and fled to safety.

Wijesinghe wasn’t having a bad day as an employee of a pest-control company. Rather, he was having a great day as a roboticist working on his final project in Northwestern Engineering's Master of Science in Robotics (MSR) program.

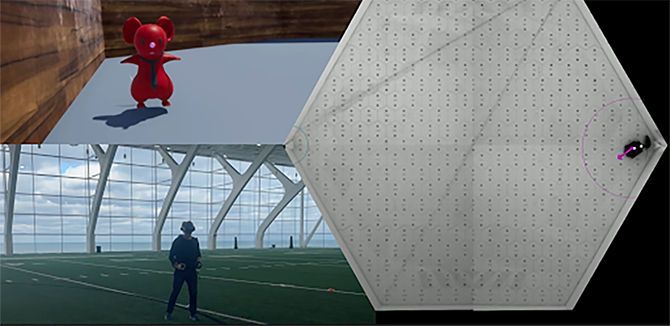

Wijesinghe’s project was a virtual–reality system that mapped his movements to a predator-like robot pursuing a mouse in the service of unlocking a deep and important mystery of how our brains work: how do brains compute strategic plans under threat? In this system, for every move he made in pursuit of the virtual mouse, a real-life robot moved in near lockstep, tracking an actual rodent.

Having that near-simultaneous reaction was key to the project’s success.

“From the get-go, we knew that this project would live or die depending on the latency of the communication between the virtual reality game and the system that governs the robot’s movement,” Wijesinghe said. “We set out to allow a human player to tele-operate a robot using virtual reality, and we did exactly that.”

While this might sound like a gamer’s dream, the research behind the project goes much deeper, seeking to understand more about how the brain plans and deals with threats.

Wijesinghe’s project grew out of the research of Professor Malcolm MacIver and Professor Daniel Dombeck, whose labs explore understanding how animals acquire sensory information and use it to guide decision-making and movement.

The hope of this research is to understand how brains are able to deal with planning and threats so efficiently. As a result, this research can bring more clarity to mental health disorders such as schizophrenia, anxiety, and addiction, where the brain’s planning systems can be compromised in favor of impulsive action. It can also help improve artificial intelligence algorithms that implement planning and possibly even enhance our own planning capabilities.

Wijesinghe's project falls into the field of biomimetics, a practice that seeks to learn from and mimic the strategies found in nature to solve human-design strategies. For Wijesinghe, the opportunity to build on MacIver’s work was the fulfillment of a personal goal.

“One of the big reasons I wanted to come to Northwestern was to work with MacIver,” he said. “I’d been interested in biomimetic robotics ever since I was a sophomore in high school, so it was a dream come true to be able to work in the MacIver lab.”

Wijesinghe worked directly with the MacIver lab and joined daily standup meetings to discuss the project's progress. He credited the lab's members with helping answer questions and providing advice about overcoming roadblocks throughout the project.

"Collaboration with peers, something the MSR program continually promotes, ended up being one of the greatest tools for this project," he said. "Being able to collaborate with the lab members, who have a deep understanding of the system, really propelled my understanding of the system.

Wijesinghe credited MacIver and MSR codirector Matthew Elwin with empowering him to find success.

“I remember being frustrated with parts of the project, and they would always be there to help,” he said. “One of my favorite memories of the project was making a breakthrough on the game and running over to Matt’s office to say, ‘I did it!’ Both of these mentors shared in the victories of the project.”

The victories were hard-won. Creating a tether-free system so a user could move around an actual landscape to control a robot in pursuit of its prey proved challenging. There were countless struggles before Wijesinghe found success.

But by the time his project was done, the work was a success.

“Perseverance and persistence were incredibly important,” he said. “I know for a fact that I will be taking these lessons wherever I go.”

Right now that place is Karagozian & Case, an engineering and scientific consulting firm where Wijesinghe works as a software engineer. There, he provides software solutions for clients in a variety of industries.

It’s a job his MSR work — especially his final project — prepared him for excellently.

“There was a particular emphasis in the interview process on having experience with real-time game engines, which my final project gave me plenty of,” Wijesinghe said. “I know I’ll be able to continue to be persistent and persevere through a lot of the problems I’ll face in my professional career.”